Your story is your life. As human beings, we continually tell ourselves stories — of success or failure; of power or victimhood; stories that endure for an hour, or a day, or an entire lifetime. We have stories about our work, our families and relationships, our health; about what we want and what we’re capable of achieving. Yet, while our stories profoundly affect how others see us and we see ourselves, too few of us even recognize that we’re telling stories, or what they are, or that we can change them — and, in turn, transform our very destinies.

Michelangelo’s David stands not only as a masterpiece of Renaissance art but as a monument to the extraordinary power of the story we tell ourselves—the story we tell ourselves about ourselves, first privately and then publicly. When I look at David, I see the embodiment of narrative self-authorship, of how our internal stories create the architecture of our identity, our courage, and the way we stand in the world.

Michelangelo sculpted David over four years, imbuing marble with the tension and spirit of a young shepherd poised to face the giant. David’s story is that of a boy no one expected to defeat Goliath, yet he is the hero who rewrites the narrative of the oppressed. His calm eyes, taut muscles, and fearless stance tell a story of belief in one’s own potential. This is the story Michelangelo carved into stone—the story “I am not defined by my size, nor by my limitations, but by my purpose and courage.”

The power of this story begins within. David’s gaze is looking off into the distance; he is not reacting but envisioning. This internal narrative is one of focus and self-command: “I am prepared. I am the victor before the battle.” The story we tell ourselves before we act conditions the outcome. Like David, our internal monologue can be a source of unshakeable confidence or debilitating doubt. The story we nurture within becomes our sword and shield.

But the story of David is not just internal; it is told to the world in every curve and vein of the statue. Public storytelling is a performance, a declaration: “This is who I am.” David’s impressive scale—larger than life—asserts presence, demanding that others acknowledge the story embodied. The statue is placed in Florence’s public square not to conceal but to proclaim the power of individual courage intertwined with collective identity.

Michelangelo’s David teaches an essential truth: the story you tell yourself shapes how others perceive you. Our self-story is a beacon or a barrier. It influences not only our self-image but the social scripts that determine where we fit in. Just as David’s poised strength inspired a republic’s hope against tyranny, our narratives influence the culture we contribute to, the relationships we build, and the legacy we leave.

An exquisite detail is David’s contemplative expression, capturing the line between youthful vulnerability and towering resolve. This duality speaks to the complexity of storytelling: it is not about perfect confidence but about holding together contradiction in our narrative identity—the doubts and the determination, the fear and the faith. Michelangelo reminds us that authentic self-stories are textured, human, and powerful.

This story also reminds me as a coach that transformation is a process of revision. David was a block of marble, undefined, until Michelangelo saw the story within and carved it out. Similarly, people often carry raw potential locked inside unshaped narratives. Coaching is the art of uncovering the hero within—the story that needs to be told, reshaped, and lived. The moment you start telling yourself “I am David facing my Goliath” is when transformation begins.

David’s story is universal. It resonates from Renaissance Florence to today’s individual challenges—starting a business, changing careers, facing personal fears. The power lies in the story you hold before you step into the arena. Will you stand small and silent, or like David, radiate presence and purpose?

The stories we tell ourselves—the ones we announce to ourselves and others—construct our lives. Michelangelo’s David is a timeless reminder that the greatest sculpture is often the one we carve from our own lives through the narratives we choose. Our story shapes the reality we create; it beckons us to stand tall, poised, and ready—not by avoiding our giants but by owning our story.

That is the power of your story.

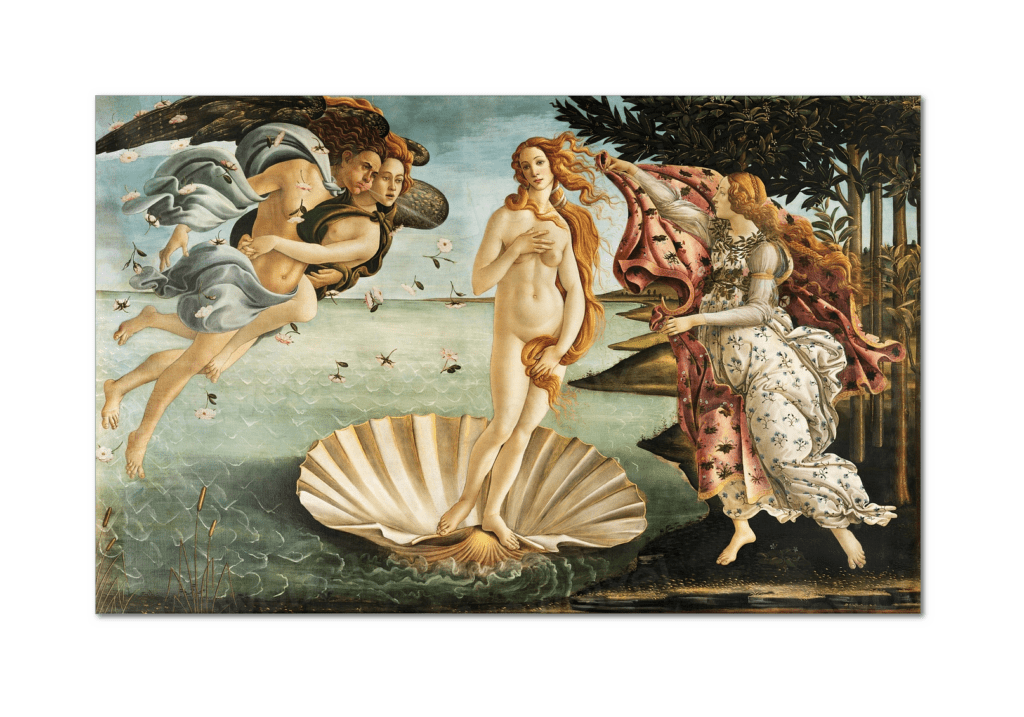

Sandro Botticelli’s masterpiece The Birth of Venus exquisitely illustrates the transformative power of the story you tell yourself—the internal narrative that shapes your sense of identity, beauty, and rebirth. When I gaze upon Venus rising from the sea, I don’t see merely myth rendered in paint and gold, but a profound metaphor for the narratives that rise within us, shaping how we face the world and ourselves.

Venus embodies the story of emergence—“I am beauty born anew, arising from chaos into form.” Botticelli captures not just a goddess but the moment of self-recognition, the internal awakening we all experience when we decide who we will be. The shell—both cradle and stage—becomes the vessel for this narrative rebirth. It symbolizes the safe space where your story grows, nurtured by imagination before it is projected into the world.

The winds that carry Venus forward represent the stories of influence around us—family, culture, history—that shape but do not define us. Yet it is Venus’s conscious emergence that tells an empowering tale: despite these external forces, the story you tell yourself about yourself is sovereign. Like Venus, you have the power to rise and shine, not as a passive effect but as a radiant subject authoring your own rebirth.

Botticelli’s Venus is both human and divine, vulnerable and powerful. This duality reflects the complexity of our self-narratives—they are never simple proclamations of strength but layered stories embracing imperfection, yearning, and transcendence. Her gaze is serene yet challenging, a silent narrative of confidence that invites the world to witness her becoming.

The figures around Venus—the Zephyrs blowing gentle winds and the handmaid offering a cloak—embody relational narratives that support or resist transformation. They remind me how our stories unfold in social contexts; our identity is constantly negotiated and reshaped in dialogue with others. The cloak symbolizes the story you choose to reveal or conceal, the aspects of yourself you nurture privately before public display.

The flowing lines and luminous colors evoke the fluidity of narrative itself. Stories are not static portraits but living currents, shifting with time and reflection. Botticelli’s mastery teaches that the story you tell yourself is a work of ongoing creation—a birth that happens again and again, inviting continuous renewal.

This painting, like great storytelling, moves beyond physical beauty to illuminate an inner journey—a story of awakening to self-love, acceptance, and emergence from past limitations. It embodies the moment when your internal narrative transfigures obscurity into brilliance.

In my coaching, I see countless individuals trapped by stories limiting their potential. The Birth of Venus beckons us to rewrite these stories—to see ourselves as rising, radiant, reborn despite hardship or doubt. It teaches that the power of your story lies not in perfect beginnings but in courageous emergence.

The power within the story we tell ourselves about ourselves—to ourselves first and then to others—shapes how we inhabit our lives. Botticelli’s Venus reminds us to hold space for this creative rebirth, to honor the chaos from which beauty is born, and to stand confidently in the radiant story we are writing moment by moment.

That is the eternal dance of narrative power—the birth and rebirth of self that The Birth of Venus so beautifully captures and that lives within each of us.

Telling ourselves stories provides structure and direction as we navigate life’s challenges and opportunities, and helps us interpret our goals and skills. Stories make sense of chaos; they organize our many divergent experiences into a coherent thread; they shape our entire reality. And far too many of our stories are dysfunctional, in need of serious editing. First, we ask you to answer the question, “In which areas of my life is it clear that I cannot achieve my goals with the story I’ve got?” We then show you how to create new, reality-based stories that inspire you to action, and take you where you want to go both in your work and personal life.

For decades I have been examining the power of story to increase engagement and performance. Thousands of individuals from every walk of life have sought out and benefited from our life-altering stories.

Our capacity to tell stories is one of our profoundest gifts. My approach to creating deeply engaging stories will give you the tools to wield the power of storytelling and forever change your business and personal life.

The Bayeux Tapestry is not just an artwork; it is a monumental story, an epic narrative embroidered in cloth—a powerful testimony to the stories we tell ourselves and others, shaping collective memory and identity. From the perspective of the power of your story—the story you tell yourself about yourself to yourself and others—the Bayeux Tapestry embodies the transformative power of storytelling across generations.

This tapestry narrates the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, stitching together battles, betrayals, alliances, and triumphs into a continuous visual saga. It is a story born of perspective—crafted to justify and glorify William the Conqueror’s claim, embodying how stories shape truth. The creators and patrons of this tapestry authored a narrative not just to record but to influence, to persuade.

In every embroidered scene, knights charge, banners fly, and tensions mount. Yet at its core, the tapestry tells the story of conquest as inevitable destiny, and the Norman as rightful hero. This underscores how group and personal identities are shaped by the stories we embrace about events and ourselves. The Norman viewcraft redefined English history, making William’s victory the foundational myth, inspiring loyalty and unity.

Reflecting on the narrative structure, the tapestry unfolds like a continuous epic poem, the scenes flowing as chapters. This continuous thread mirrors how our personal and collective stories are woven over time, each event shaped by the story that came before and influencing the one after. It reminds us that no story stands alone; we are always authors of an ongoing narrative.

The power of this story reaches into identity—those who wore armor under the tapestry’s shadow would have internalized the Norman tale as a call to destiny, shaping how they saw themselves as conquerors, rulers, and builders of a new order. This internal narrative empowered them with a sense of purpose and legitimacy.

Yet beneath this militaristic story, subtle details humanize the tale—expressions, gestures, everyday customs—reminding us that storytelling is not only about grand design but lived experience. This layered narrative richness allows viewers not only to see history but to inhabit it, to experience the awe, fear, and hope of those times.

The Bayeux Tapestry as a living story illustrates storytelling’s supreme power: it shapes perception, identity, morality, and history itself. It stands as a reminder that the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves—whether in moments of personal challenge or collective upheaval—mold how we engage with the world.

When you see the tapestry, know the story behind the thread—the power to author reality in image and word is as old as civilization. What story do you weave about yourself? How does your narrative inspire or constrain your destiny?

That is the enduring magic of Bayeux: storytelling made visible, learning that the power of your story is the power to transform the world around you.

The caves of Lascaux hold one of humanity’s most ancient and profound stories—a story told not through words but through images, shapes, and symbols etched deep into stone walls. From the perspective of the power of your story—the story you tell yourself about yourself to yourself and others—Lascaux invites us to reflect on how storytelling is foundational to human identity, meaning, and survival.

Imagine those early humans standing before the vast cavern walls, painting majestic bulls, stags, and horses with ochres and charcoal. These were not just artistic expressions but narratives—stories about the world, their relationship to nature, the hunt, and possibly spiritual or ritualistic visions. These images communicated their collective identity, hopes, and fears at a time before language or writing. They told themselves: “We belong to these lands. We are hunters and keepers of life’s cycles.” This internal narrative anchored their place in the world.

Lascaux’s story is one of connection—between humans, animals, environment, and spirit. The paintings capture a dynamic interface where humans narrate their existence, transcending immediate survival to weave meaning. This reveals how the earliest stories shaped not only memory but identity: “We are part of a sacred whole.” The caves became a narrative sanctuary, a place where personal and group stories coalesced into ritualized meaning.

The structure of Lascaux’s storytelling is non-linear and visual. Unlike the linear stories of later literature, here, narrative flows through symbolic repetition, layout, and interplay of images—foreground and background, light and dark—engaging viewers in immersive storytelling. This architectural storytelling shows that narrative is not confined to text but is spatial, sensory, and communal. Stories circulate, unfold and interact through space and time.

The power of this ancient story was survival. These painted narratives may have been rites to ensure hunting success, to teach young hunters the life story of prey animals, or to mark territorial belonging. The story humans told themselves gave them confidence and cohesion necessary to endure physical and existential threats. It was not only a story told to others but a story reinforced nightly around fire—a collective heroic journey from dusk to dawn.

Lascaux teaches us that storytelling is intrinsic to being human; it is the first step in authoring identity out of chaos. Before words, images told stories of who we are and who we aspire to be. Our internal narratives, even now, follow this ancient impulse—to claim agency by telling stories that link us to place, to community, and to the cosmos.

For us today, amidst digital flood and information overload, Lascaux’s silent walls remind us to reconnect with the primal power of storytelling: to pause, reflect, and create meaning. When you tell yourself your story—who you are, what you stand for—you are continuing a tradition thousands of years old, stamping your being into the fabric of existence.

The magic of Lascaux lies in its testimony that the story you tell yourself about yourself—spoken or painted, internal or shared—shapes your reality, your courage, and your legacy. It invites you to ask: what ancient stories live inside you, waiting to emerge? What walls will your stories paint across the canvas of life?

That is the profound lesson of Lascaux—the power to narrate change, to encircle fear with meaning, and ultimately, to author identity in the face of the unknown. Your story is your most enduring art.

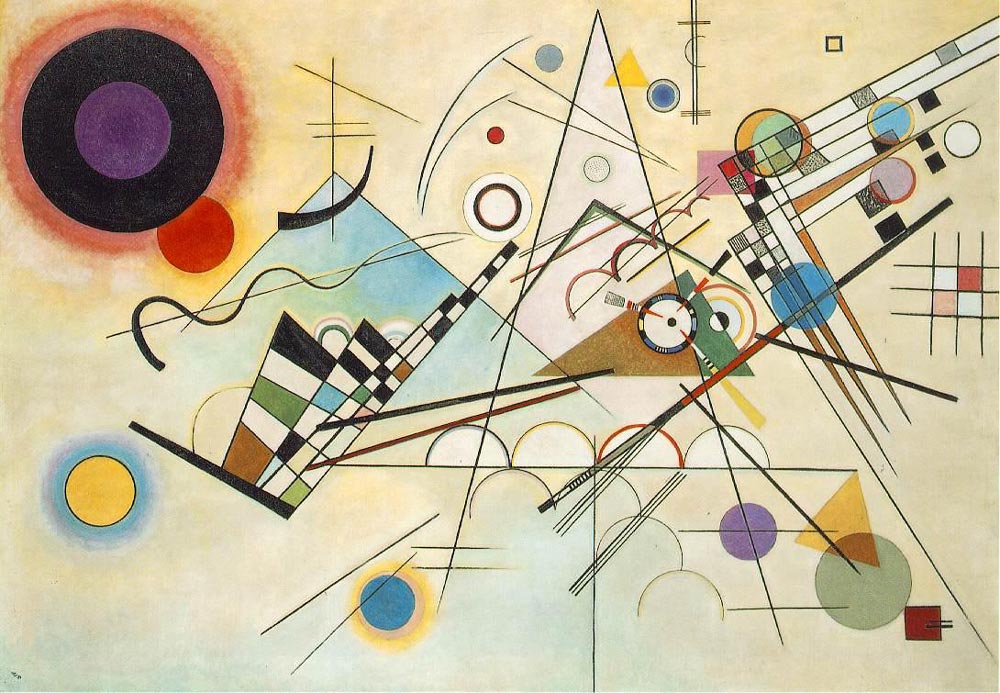

Wassily Kandinsky’s masterpiece Composition VII is a vivid celebration of the power of your story—the story you tell yourself about yourself and then project into the world—which transcends language and literal form to shape your inner reality and creative expression. This complex, swirling explosion of colors and shapes offers a profound metaphor for the living, dynamic narratives that define us.

Composition VII is often regarded as Kandinsky’s most intense and multifaceted work. Its tangled forms and vibrant palette suggest chaos and conflict, yet beneath the surface lies a story of transformation—a journey from disarray to harmony. It mirrors the deep tension in our own lives: competing emotions, conflicting desires, storms of doubt—all woven into the fabric of our identity story.

When you look closely, the painting reveals no simple linear path but a constellation of forces pushing and pulling like the competing voices in your internal monologue. Just as your story unfolds not as a straight line but as overlapping, sometimes contradictory experiences and emotions, Kandinsky’s Composition VII honors the complexity of self-narrative.

Kandinsky once wrote that color has a soul, lines have their own language, and art should evoke the spiritual. In Composition VII, these elements become the language of your story’s soul—a non-verbal communication of what cannot be fully articulated in words. This encourages embracing the unspoken, the intuitive, and the symbolic parts of your narrative.

The painting’s movement suggests the hero’s passage through the chaos—the Abyss—before reaching a new form of selfhood, a moment of synthesis where disparate elements become an Elixir of insight and renewal. This is the power of your story during transformation: chaos precedes clarity, confusion births growth.

More than a static picture, Composition VII is a dynamic story in color and form, alive and evolving. It reminds us that the stories we live by are not final but fluid and layered. You are the continual author of your narrative—able to reshape, reinterpret, and re-express your identity through ever-changing internal and external stories.

When I teach narratives, I use Composition VII to show that story is not confined to words; it lives in sensations, emotions, and abstractions. The power of your story is not only in the tale you write but in how you embody it—in your energy, your vision, your presence.

Kandinsky’s masterpiece challenges us to reclaim storytelling as a sacred, creative act capable of shaping reality itself. In a world obsessed with facts and logic, Composition VII invites you to listen to your soul’s colors and lines—to tell your story in the richest language possible.

Ultimately, Composition VII stands as a monument to the power of your story—not a neat tale but a bold, vibrant, living force—that shapes your world, your identity, and your destiny through the art of narration beyond words.

Day 1. That’s Your Story?

Day 2. The Premise of Your Story, the Purpose of Your Life

Day 3. How Faithful a Narrator Are You

Day 4. Is It Really Your Story You’re Living?

Day 5. The Private Voice

Day 6. The Three Rules of Storytelling

PART TWO

New Stories

Day 7. It is not about time

Day 8. Do You Have the Resources to Live Your Best Story?

Day 9. Indoctrinate Yourself

Day 10. Turning Story into Action: Training Mission and Rituals

Day 11. More than Mere Words; Finishing the Story, Completing the Mission

Day 12. Storyboarding the Transformation Process in Eight Steps

Introduction

I am Peter de Kuster, founder of The Hero’s Journey and The Heroine’s Journey, and for much of my life, I have believed in the transformative power of stories—especially the ones we tell ourselves. But it took a near-death experience to truly open my eyes to what I wanted to dedicate my life to: helping others discover, shape, and share their unique stories, and in doing so, to rewrite my own.

Antoni Gaudí’s masterpiece, the Sagrada Família, serves as a magnificent testament to the power of the story you tell yourself—the story you craft about who you are, what you create, and how you leave a legacy that transcends time and circumstance. This monumental basilica in Barcelona is not just architecture; it is a living narrative in stone, light, and form, representing how deeply our internal stories shape the world we build around us.

Gaudí began with a vision fueled by his inner story—“I am an instrument of nature’s divine geometry; I will build a cathedral that speaks the language of life itself.” The Sagrada Família embodies this personal narrative: a story of devotion, patience, creativity, and faith that guided Gaudí’s life and work. Despite challenges, delays, and critiques, he held fast to his story, allowing it to define both his purpose and his legacy.

Every column, spiral, and stained-glass window tells a part of Gaudí’s internal story translated outward. His design mimics forms of nature—trees branching upward, light flowing like water—revealing that the story he told himself connected transcendence to the tangible, sacred to the everyday. By telling himself this story of organic, harmonious creation, Gaudí redefined what a cathedral could be: a living, breathing narrative space inviting awe and introspection.

The Sagrada Família’s slow, unfinished construction exemplifies the ongoing narrative process: stories are never complete but evolve across lifetimes. Gaudí embraced a long view—“My story is larger than one lifetime”—modeling how personal narratives propagate and inspire beyond our immediate presence. This chapel-in-progress calls us to participate in storytelling as a communal and generational act.

Gaudí’s masterpiece also speaks to the narrative tension between individuality and community. His personal vision balanced with collaborative craftsmanship reflects how internal stories intersect with shared culture and values. The basilica stands as both personal manifesto and collective heritage—a dialogue across time between artist, faith, and people.

Through the emotive play of light refracted by vibrant glass, Gaudí’s story merges science and spirituality, reminding us that the stories we tell about ourselves also shape how we perceive beauty, meaning, and the divine. His art transcends words, using form and color as language—a vivid metaphor for the nonverbal narratives pulsing within each of us.

For me, Gaudí’s Sagrada Família is a living metaphor: the story you tell yourself about your creativity, your mission, and your capacity to shape the world can sculpt wonders, endure centuries, and inspire countless others. It teaches that the power of your story is revealed not just in what you say but in what you build, embody, and leave behind.

Standing before the soaring towers and intricate facades, I hear Gaudí whisper, “Author your story with patience and passion; let it grow like a tree from your soul into the sky.” This is the call for every storyteller—to see themselves not as mere narrators but as architects of their own lives, capable of shaping realities as enduring as stone, as luminous as stained glass.

The Sagrada Família invites you to tell your story boldly, to build it with reverence and resilience, knowing it will stand beyond your lifetime. Your story, like Gaudí’s basilica, is an eternal work of art, waiting to be born and to transform the world.

Lying in that hospital bed, suspended between what was and what could be, I realized how fragile and precious life is. All the plans, the business meetings, the deadlines—they faded into insignificance. What remained was a burning question: What story do I want to tell with the rest of my life? The answer was clear. I wanted to travel, to write, to tell stories.

There is a language older than words that has always fascinated me. It speaks in images and emotions, in the quiet tightening of a throat in a dark cinema, in the sigh when the credits roll and you realize the story on the screen has quietly rewritten a sentence in the story you tell about yourself. Like in Dead Poets Society, where students seize the day, ripping out textbook pages to embrace poetry’s raw power over conformity, sparking personal rebellion and self-discovery. That is the language I am searching for with The Power of Your Story: a universal language of stories that crosses borders, backgrounds, and biographies, and invites each of us to become a better storyteller of our own life.

My quest runs through movie palaces in Rome, side streets in London, quiet museums in Venice, and cafés in Amsterdam, where people sit with notebooks, watching scenes from great films and quietly recognizing themselves. In these story-rich places, I walk with entrepreneurs, artists, and seekers who arrive with a familiar question hidden behind their official goals: “Why does the story I am living not feel like mine anymore?” Together we watch heroes and heroines on the screen and notice that, beneath costume and culture, they share something startlingly similar: seven great plots, twelve archetypal heroes, and again and again one great story about leaving an old life behind to claim a truer one.

Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People is more than a masterpiece of revolutionary art; it is a monumental testament to the indomitable power of the story you tell yourself—the narrative that defines your identity, your purpose, and your capacity to lead and inspire change. When I, Peter de Kuster, gaze upon Liberty’s fierce stride across the barricades, I see the embodiment of narrative courage—the story told first to oneself, then projected outward, rallying and reshaping communities and destinies.

At the painting’s heart is Liberty herself, a towering figure with bare breast bared defiantly, the French tricolor flag streaming above her, musket and saber at the ready. She does not cower before the chaos of revolution; she is its beating heart. Her posture, poised yet dynamic, carries the undeniable message: “I am not a victim of circumstances. I am the embodiment of freedom, the leader of a cause greater than any one individual. Step into this story with me.” This is the power of personal narrative—the story that fuels resilience and leadership even amid smoke, blood, and danger.

The study of Liberty’s internal storytelling begins with her gaze: fixed, fierce, and unyielding. She is envisioning victory, marshaling resolve before battle is even joined. This is the core of powerful personal stories—precognition, the ability to mentally script not only where you stand but where you move next. You author the narrative from inside your mind before any external action occurs. Liberty is not reactive; she is the author of destiny.

The crowd behind Liberty is a living canvas of narrative diversity gyrating into unity. Look closely and notice the juxtaposition: a boy with pistols too large for his small frame, embodying the story of inherited courage and youth stepping into a saga not of their making, a working man with clenched fists and sleeves rolled, and a well-dressed bourgeois sporting a top hat, abandoning privilege to join the cause. Liberty’s story magnetizes these disparate lives, weaving individual narratives into one collective function. Such is the social magic of narrative: it shapes not just self but community, building bridges between isolation and shared purpose.

Delacroix’s composition itself is storytelling architecture. The diagonal thrust from the barricade’s rubble upward to Liberty’s lead foot commands the eye and signals progression—from the chaos-laden Abyss of revolt to the Call to Adventure manifest in Liberty’s emergence. Fallen comrades littering the foreground symbolize sacrifice, grounding idealism in harsh reality. This is storytelling with stakes—your narrative is never costless, and honor lies in what you endure or lose to see your story through.

The French tricolor flag is not a mere decoration. It’s narrative compression—the summing up of complex ideals into instantaneous, emotionally resonant symbols. Blue for liberty, white for equality, red for fraternity and sacrifice. Liberty’s firm clutch on the flag signals narrative ownership; this is not a story she borrows but one she commands. Extract the lesson here: your story’s symbols and metaphors become the language by which it rallies others. Whether it is a company logo, a personal mantra, or a cultural icon, these symbols crystallize the story and its emotional power.

Light in the painting plays a narrative director. Liberty’s glowing torso and radiant flag emerge from the smoky twilight—a selective illumination that focuses the viewer’s attention on what matters most: the hero, the cause, the symbol. This spotlighting teaches us a crucial lesson: a story’s power is maintained by what it chooses to highlight and what it obscures. A compelling narrative consistently brings core truths to light while leaving distractions in shadow.

Liberty’s deliberate bare-breasted vulnerability shatters conventional ideas of power. Instead of concealment, exposure becomes armor—a courageous declaration that authenticity and boldness fuel strength. There is a lesson here about the raw, unguarded parts of your story. The moments you might feel exposed or vulnerable are often the source of your greatest power and connection.

The child brandishing oversized pistols represents the generational nature of story. This young warrior’s narrative is inherited and shapes his identity, reminding us that the stories we author today will echo beyond us, passing from one generation to the next, influencing futures we may never see.

In stark contrast to Liberty’s fearless vitality, the fallen bodies ground the scene in the costliness of storytelling. Their deaths remind us that narratives demanding transformation often carry sacrifices. Honoring those costs in your story adds depth and authenticity—true leadership recognizes and reveres what has been lost.

The contested terrain of the barricade itself is a powerful metaphor for narrative reclamation. It is the fractured ground where old stories of submission and obedience clash violently with emergent stories of defiance and freedom. Liberty’s act of claiming this space is symbolic of how powerful narratives seize control of contested cultural or psychological territory, rewriting reality.

The dynamic forward momentum—the diagonal line sweeping upward, the raised tricolor, the purposeful stride—impose narrative inevitability. Powerful stories require full commitment; hesitation weakens and dissolves influence. Delacroix’s Liberty doesn’t pause; she’s irreversible in purpose, reminding us stories don’t just describe realities, they shape and change them.

The joyous, defiant expression on Liberty’s face offers a profound truth: rage can spark revolution, but joy sustains it. The story you tell yourself with joy and conviction will outlive one told in bitterness or despair.

Delacroix’s painting was born of personal and political upheaval. Painted during the 1830 July Revolution, the work was censored by the authorities and later reinstated as a symbol of republican resilience. This journey parallels the life of any powerful story: initially misunderstood or suppressed, only to later emerge as a beacon of hope.

Modern parallels abound. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech channels Liberty’s narrative arc, drawing on shared ideals to envision change. Rosie the Riveter’s iconic “We Can Do It!” poster calls women into a collective story of empowerment. Visionary entrepreneurs and political leaders today use similar storytelling patterns—authoring change, rallying disparate groups, creating shared visions.

Understanding Liberty’s story provides a framework for revolutionary storytelling:

- Bold emergence from the darkness of the past.

- Inclusive rallying of diverse voices and experiences behind a unified narrative.

- Symbolic weaponry that distills complex ideals into a compelling icon.

- Honoring sacrifice, acknowledging costs as foundational to the story’s depth.

- Forward momentum, creating unstoppable progress and inviting continued movement.

Liberty Leading the People does not ask you to passively observe. It calls for choice: to lead or follow, to author your narrative or live one imposed. The stories we tell ourselves about ourselves don’t just mirror the world—they build it.

The question it leaves us with is urgent and personal: What is your story? What flag will you raise, and who will follow your charge?

Through smoke, blood, unbreakable stride, Liberty Leading the People reveals that storytelling is our most potent weapon—a force capable of transforming chaos into collective conquest. What giants do your stories make you charge?

That is the power of your story—the story you tell yourself, and then others—which becomes the legacy you live.

What fascinates me is how the same story patterns keep appearing in people who have never met. A designer in Berlin talks like a Warrior exhausted by endless battles for recognition. A chef in Barcelona feels like the Orphan, forever on the edge of belonging. A startup founder in Paris discovers she has been living the Ruler’s story of control when her heart longs for the Explorer’s open road. Then we sit in a cinema and watch a character in a film struggle with the very same script. In La Vita è Bella, a father shields his son from Holocaust horrors by framing camp life as an enchanted game, turning despair into defiant love and survival. In that moment, the language of story becomes universal: you no longer feel uniquely stuck; you feel spoken to. The film is no longer “about” someone else. It is a mirror, gently asking: “Is this the story you still want to live?”

In The Power of Your Story, I always begin with one question: “In which areas of your life is it clear that you cannot achieve your goals with the story you’ve got?” It is a brave question because it exposes the hidden contracts we live by: “I must always please,” “I must never fail,” “I am only valuable when I achieve.” As people answer, you can feel the old plot loosening its grip. Then, using the archetypes and classic plots from film, we start drafting a new premise: What if your life is not a tragedy of overwork but a quest for meaningful creation? What if your business is not a battlefield but a love story with your best customers? What if your leadership is not about power but about pilgrimage—inviting others on a journey that matters?

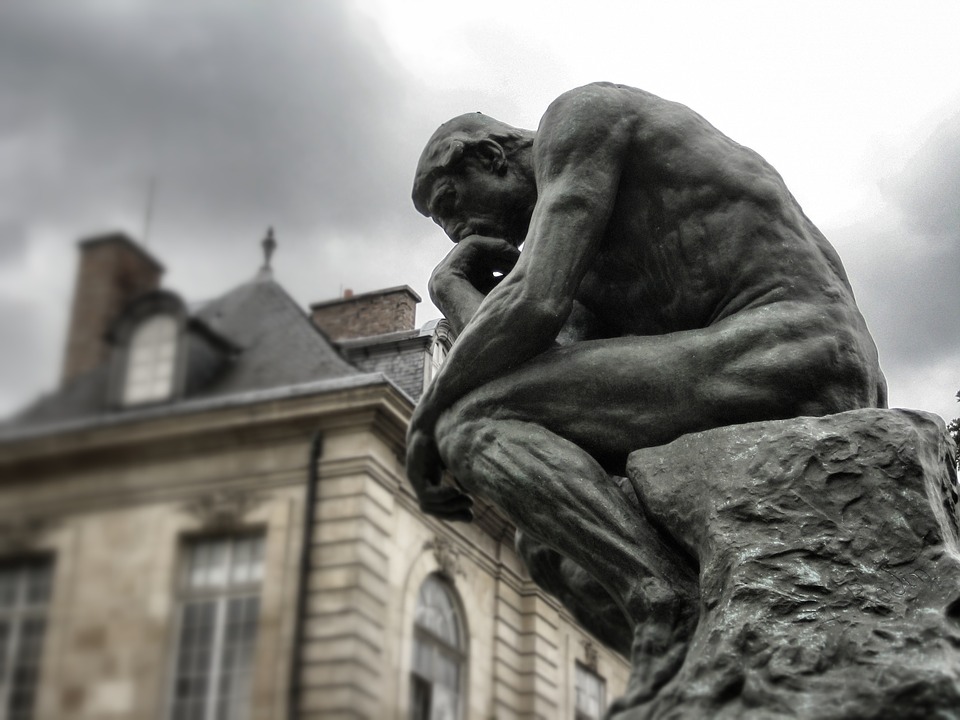

Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker stands as a silent monument to the power of the story you tell yourself—the deep, internal narrative of reflection, choice, and becoming that shapes who you are and how you move through the world. When I, Peter de Kuster, consider this iconic sculpture, I see not merely a man lost in contemplation but the embodiment of the profound inner dialogue that defines the human experience.

The Thinker captures the moment of pause within the Hero’s Journey—the critical stage where you confront the abyss, wrestle with doubt, and decide whether to carry forward. His hunched posture, hand pressed firmly to his chin, is the physical manifestation of intense self-reflection—the narrative alchemy where confusion begins to clarify, questions birth insight, and stories twist toward transformation.

This sculpture teaches the most essential storytelling lesson: the stories you tell yourself first live within your mind before they ever shape actions or narratives told to others. The Thinker’s gaze is downward, not on the external world but into the depths of his inner world—his thoughts, fears, hopes, and desires all swirling in silent conversation. What story is he telling himself about himself? Is it one of doubt or emerging clarity, paralysis or purpose?

Rodin’s masterpiece also reminds us that storytelling is a process—a dialogue, not a monologue. The thinker’s solitary pose masks a rich internal drama. He questions every assumption, challenges every certainty. This internal narrative wrestling is not weakness but courage—the willingness to confront uncertainty with honesty. In this liminal space, your story is malleable, offering a chance to rewrite identity, decisions, and destiny.

Beyond the thinker as individual is the universal story of human agency: to choose is to create your story. The sculpture becomes a symbol of free will and self-authorship, embodying the moment when you decide how to respond to your calling, your trials, your abyss. It challenges the myth that action equals power, revealing instead the narrative potency of thoughtful pause.

The power of this story lies also in its invitation to embrace contradiction: the thinker is both burdened by and empowered through reflection. His tense muscles suggest struggle, yet his stillness evokes calm insight. Your internal story, too, must hold tension—between fear and hope, doubt and courage—to grow.

In coaching, The Thinker inspires deeper inquiry into personal narratives. When clients feel stuck, I urge them to occupy their inner thinker: to hold space for their stories with curiosity rather than judgment. This quiet courage plants seeds for transformation that action alone often cannot.

Rodin’s work also speaks to cultural storytelling. It stands on the threshold between ancient mythic heroes and modern existential self-awareness. The thinker is Orpheus reimagined for modernity—no longer leaping into battle blind, but gazing inward for meaning. This shift reflects our evolving narrative needs: from heroic deeds to authentic selves.

Light and shadow shape The Thinker—his form catching nuanced highlights and deep darkness. This chiaroscuro mirrors storytelling’s play between revelation and concealment, known and unknown. Your story is illuminated in moments of insight but often exists in shadows—waiting patiently for the telling.

The scale of the sculpture—larger than life—declares the immense weight of internal storycraft. This is not trivial self-talk but the epic forging of identity. Your inner narrative is the foundation upon which all else stands.

Ultimately, The Thinker symbolizes storytelling’s sacred act: the continuous turning inward to clarify and reclaim your self-story. It teaches that the power of your story lies not only in how boldly you narrate it externally but in the depth and truth you cultivate within.

The story you tell yourself in moments of solitude, doubt, and questioning becomes the force that shapes your life’s journey.

In the silent contemplation of The Thinker, we witness the universal hero’s moment—when reflection births action, hesitation becomes resolution, and the story of self is forged anew.

That is the power of your story—the story held inside, the story told outward, the story that becomes your legacy.

What this quest can bring all of us is not a neat formula, but a toolkit and a courage. The toolkit consists of questions and structures: the premise of your story, the words on your future tombstone, the mission you dare to say out loud, the archetype that best expresses your values, the plot that truly fits the season of life you are in. The courage comes from realizing you are not alone: every great story, every great business, every meaningful relationship has had to rewrite itself at some point. When you start to see your life as a work in progress rather than a verdict, you reclaim authorship. You stop asking, “What is happening to me?” and start asking, “What story am I telling—and what story do I want to tell next?”

The universal language of stories is, in the end, a language of choice. You cannot control every event, every loss, every unexpected twist. But you can choose the story that gives those events meaning. My work, and my joy, is to walk with people through the great cities and great movies of the world until they can hear that language clearly in themselves. When they do, something simple and astonishing happens: they stop trying to live someone else’s script. They become the storyteller, not just the character. And from that moment on, their business, their relationships, and their inner life begin to align around a new, truer story—one only they can tell.

What do I mean by ‘story’?

What do I mean by ‘story’? I don’t intend to offer tips on how to fine-tune the mechanics of telling stories to enhance the desired effect on listeners. And I do not mean the boiler-plate, holier-than-thou brand stories often found in the Mission Statement of corporate websites, or the Here’s -why-we’ll – absolutely-meet-our-fourth-quarter numbers-narrative-yarn-turned-pep-rally that team leaders often like to spin to rally the troops.

No, I wish to examine the most compelling story about storytelling – namely how we tell stories about ourselves to ourselves. Indeed, the idea of ‘one’s own story’ is so powerful, so native, that I hardly consider it a metaphor, as if it’s some new lens through which to look at life. Your life is your story. Your story is your life. When stories we read or watch or listen to are triumphant, they are so because they fundamentally remind us what is most true or possible in life – even when it is an escapist romantic comedy or sci-fi fantasy or fairy tale. If you are human, then you tell yourself stories – positive ones and negative, consciously and, far more than not, subconsciously. Stories that span a single episode, or a year, or a semester, or a weekend, or a relationship, or a season, or an entire tenure on this planet. Telling ourselves stories helps us navigate our way through life because they provide structure and direction. ‘Just seeing my life as a story’ said one of my clients ‘allowed me to establish a sort of road map, so when I have to make decisions about what I need to do [the map] makes it easier, takes away a lot of stress’.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is an enduring masterpiece that captures the timeless power of the story we tell ourselves—the internal narrative that shapes our identity, our emotions, and how we present ourselves to the world. When I, Peter de Kuster, reflect on the Mona Lisa, I see more than a portrait; I see a profound exploration of the story of self—the delicate balance between mystery and revelation, presence and enigma.

Mona Lisa’s subtle smile is the heart of this narrative power. It is neither overt delight nor secretive concealment but a living story suspended between ambiguity and invitation. This smile embodies the inner story she tells herself—a story of composed confidence, quiet strength, and the acceptance of complexity within. It tells us that who we are is never fully transparent, yet our stories ripple through our expressions and presence, inviting others to engage with our mystery.

Leonardo’s technique, especially his use of sfumato, blurs the lines of form to soften edges and dissolve certainty. This visual ambiguity mirrors the fluidity of our self-narratives. Just as Mona Lisa’s smile can seem different from every angle, so too does our inner story shift with time, context, and reflection. The painting reminds us that our story to ourselves can change, that identity is layered and not fixed.

The gaze of Mona Lisa pulls the viewer into a silent conversation. She looks out not just with eyes but with the full force of her narrative—calm, steady, knowing. This gaze is a testament to how the story you tell yourself fosters presence and invites connection. Your self-narrative is both anchor and beacon, grounding you and drawing others.

Beyond the woman, the ethereal landscape in the background suggests the vastness of the narrative journey. Winding paths and distant horizons speak to the stories unwritten, the internal explorations that shape who we are beneath the surface. This backdrop emphasizes that your story is ongoing, a journey into unknowns that you navigate moment by moment.

Leonardo’s mastery in detail—the delicate hands, the subtle textures of skin and fabric—expresses the narrative richness of being human. Our stories are articulated not only in words or grand acts but in small gestures, nuances of posture, and expressions. Every detail of your narrative matters.

The enigmatic quality of the Mona Lisa has sparked centuries of debate, symbolizing how narrative is often contested and interpreted differently by each observer. Your story, too, will be seen through many lenses. The power lies in owning your narrative while allowing room for dialogue and evolution.

In coaching, I draw on Mona Lisa to illustrate the importance of embracing complexity in personal stories—accepting the parts of yourself that are mysterious or evolving rather than rushing to define or simplify. True narrative power thrives in this delicate balance between knowing and exploring.

Leonardo’s Mona Lisa teaches us that the most profound stories aren’t declarations shouted from the rooftops but subtle, layered, resilient narratives that invite ongoing engagement and interpretation. Your story is living art, crafted in moments and perceptions, unfolding indefinitely.

Standing before this masterpiece, I am reminded that the most powerful story you tell yourself is the one that holds space for mystery and light, that dares to look outward while exploring inward. Just like Mona Lisa, your story invites others into a dance of meaning, connection, and presence.

That is the eternal power of your story—complex, evolving, and irresistibly alive.

Edgar Degas’s masterpiece, The Ballet Class, is a vivid portrayal of the stories we tell ourselves about discipline, grace, aspiration, and the subtle complexities beneath perfection. Through the poised dancers and the watchful eye of the master, Degas captures the intimate narrative moments where identity and self-perception intersect with struggle and artistry—a powerful metaphor for the internal story you tell yourself about who you are and who you strive to be.

When I view The Ballet Class, I see more than dancers in motion; I see a silent dialogue of striving that echoes all our human narratives. The young ballerinas are caught between their current selves and the stories they hold within—stories of potential, fear, ambition, and the quest for excellence. Their delicate movements, some tentative, some confident, express the tension between vulnerability and mastery—the very essence of the stories we craft as we grow.

The ballet master, positioned with a critical yet guiding gaze, embodies the external narratives and expectations that shape our internal monologues. His watchfulness represents the societal and internal critic whose voice can either reinforce self-doubt or propel narrative growth. Our stories do not unfold in isolation—they are constantly influenced by the feedback we receive and the standards we impose on ourselves.

The subtle interplay of light and shadow in the painting mirrors the dualities present in our stories: moments of clarity and obscurity, confidence and insecurity. Degas’s brushstrokes, often described as impressionistic yet precise, reflect the fluid and layered nature of self-narrative—it flickers between definitive and ambiguous, concrete and elusive.

Each dancer’s posture tells a different story. Some stand tall and focused, their story one of rising confidence and determination. Others bend or shift, revealing narratives of self-questioning and tentative self-expression. The collective tableau shows how individual stories coexist, overlap, and influence the group’s dynamic, much like the stories we tell ourselves within our families, teams, or organizations.

This masterpiece reminds us of the power of the story not only in moments of triumph but in the quiet, uncelebrated efforts—the rehearsals, the falls, the repetitions—that are the backbone of transformation. The ballet class is not just performance; it is preparation, narrative work in progress, the Hero’s Journey in its early Trial phase, rich with both promise and struggle.

Degas also captures the timeless tension between aspiration and reality. The young dancers dream of mastering their craft, telling themselves stories of future glory, yet the painting shows the disciplined, sometimes harsh reality of training. This tension teaches that powerful narratives embrace both hope and honesty and that the story you tell yourself must acknowledge struggle to nurture resilience.

In coaching, The Ballet Class inspires the recognition that your internal story is often formed in these subtle moments—the rehearsals of your life where you practice roles, confront doubts, and hone purpose. The narrative you nurture in the backstage of your mind is as vital as the story you perform in the spotlight.

Degas’s work teaches us to honor the process of storytelling itself—the unseen, imperfect, and evolving journey of self-creation. The power of your story lies not in flawless chapters but in the authenticity and persistence of your becoming.

When you look at The Ballet Class, remember that each moment, each step, each breath is a narrative building block. The dancers invite you to see your own journey as a delicate balance of grace and grit, vulnerability and willpower, shadow and light.

That is the lesson the painting imparts—the eternal power of your story to shape identity, inspire courage, and choreograph the dance of your life. Like the dancers, you are the artist and the hero of your unfolding narrative, moving ever closer to the mastery and meaning you envision.

Ancient Greek art offers timeless wisdom about the power of the story—the story you tell yourself about yourself to yourself and others—as the foundation of identity, legacy, and human aspiration. One masterpiece that speaks profoundly to this is the Discobolus (Discus Thrower) by Myron, a sculpture that captures narrative and selfhood in poised motion.

The Discobolus is not just a figure frozen in athletic action; it is a monument to controlled potential and narrative possibility. The athlete’s body, taut and coiled, embodies the story of disciplined preparation—the story of a person telling themselves, “I am strength, balance, and focus. I am ready to cast my destiny.” The sculpture captures anticipation—the moment before release—symbolic of the transformative power inherent in the stories we narrate to ourselves.

This poised tension is the inner dialogue of the Hero’s Journey, the charged silence before crossing thresholds and facing trials. The story we tell ourselves is often not about where we stand but about where we are about to leap, and the Discobolus crystallizes this universal narrative moment.

The statue’s idealized form communicates a narrative of perfection and harmony, reflecting Greek values of arete—virtue, excellence, the fullest expression of human potential. By telling himself a story of excellence, the athlete asserts a narrative power that transcends mere physicality; it becomes an expression of identity and worth.

The narrative conveyed is both intensely personal and deeply communal. The athlete is preparing for an act that will be witnessed, judged, and remembered—signaling that our self-story is inevitably intertwined with the narratives reflected back by others. Greek art teaches that identity is co-authored not only within but among the polis, the community of shared stories and values.

Myron’s mastery lies in merging dynamism and stillness—a visual metaphor for the balance the inner story must hold between action and reflection, confidence and humility. Just as the Discobolus holds poised energy, your narrative lives in this balance, continually poised between past practice and future aspiration.

This sculpture reminds me that the stories we tell ourselves are active forces shaping how we engage with the world. Your internal narrative is a preparatory act, a readied tension that primes you for transformation. Yet it is also a public declaration, inviting witness and legacy. The Discobolus does not merely perform—it narrates a timeless human drama of struggle and grace.

In coaching, I often evoke the Discobolus as a symbol of the narrative moment when preparation and courage converge. We are all athletes in our own stories, charged with mental and emotional discipline as much as physical. Before you launch into your next phase, what story do you tell yourself about your strength and readiness? How do you harness your poised energy?

The Greek ideal embodied in Discobolus also challenges us to seek harmony in our narratives—to integrate mind and body, thought and impulse, reflection and action. The story you cultivate is valid when it sustains balance, enabling ongoing movement without collapse.

This ancient masterpiece stands not only as athletic perfection but as a metaphor for narrative sovereignty—the power to author your identity with grace, focus, and intention. To stand poised, embody your story fully, and pursue your destiny with intention.

The story you tell yourself about yourself—your strength, your purpose, your preparedness—radiates from within. Discobolus reminds us: the power of your story is born in the poised silence before launch, in the harmony of form and will, in the timeless leap toward becoming.

Through this iconic form, Greek art teaches that our stories are not just reflections but active forces—stories that shape us, propel us, and inscribe our place in history.

Your story can become your masterpiece. What narrative do you balance and prepare to release?

Indeed we are actually wired to tell stories: The human brain, according to a New York Times article about scientists investigating why we think the way we do, has evolved into a narrative-creating machine that takes ‘whatever it encounters, no matter how apparently random’ and imposes on it ‘chronology and cause-and-effect logic’. Writes Justin Barrett, psychologist at Oxford University, ‘We automatically and often unconsciously look for an explanation of why things happen to us and ‘stuff just happens’ is no explanation’ (which feeds one possible theory for why we need, or even create, God or Gods). Stories impose meaning on the chaos; they organize and give context to our sensory experiences, which otherwise might seem like no more than a fairly colorless sequence of facts. Facts are meaningless until you create a story around them.

Rembrandt’s masterpieces, especially his self-portraits, capture the profound power of the story we tell ourselves—the internal narrative shaping our perception, identity, and ultimately how we present our true selves to the world. From my perspective as Peter de Kuster, Rembrandt’s art offers a timeless lesson on owning your story with honesty, vulnerability, and unflinching introspection.

Rembrandt painted himself across decades—each self-portrait a chapter in his evolving internal narrative. The aging artist stares out from the canvas with eyes that reveal wisdom and struggle, confidence and doubt. In this gaze lies the heart of storytelling power: the courage to tell yourself not only who you wish to be but who you really are, embracing flaws alongside strengths.

The layering of paint mirrors the layers of identity constructed and deconstructed over time. Rembrandt’s use of chiaroscuro—dramatic light and shadow—literalizes how our narratives often illuminate some truths while obscuring others. Our self-story is never fully visible at once; it reveals itself gradually, in moments of reflection and confrontation.

What moves me deeply is Rembrandt’s refusal to shy away from vulnerability. His portraits are honest—they show success and suffering, pride and despair. He models narrative authenticity: that the stories we tell ourselves are most powerful when they acknowledge complexity rather than perfection. This invites us to own not only our triumphs but also our shadows, weaving them into a richer, more compelling story.

Through his brushstrokes, Rembrandt captures the silent dialogues we hold within—between confidence and fear, hope and regret, past and future. This internal narrative tension propels growth; it is the crucible in which our story is forged anew with every passing year.

Rembrandt’s self-portraits also engage the viewer in a relational narrative. His stare challenges us to see beyond surfaces, inviting empathy and recognition of shared human experience. This reminds us that the story we tell ourselves inevitably connects with the stories others tell about us, creating an ongoing dialogue shaping how identity is perceived and lived.

In my coaching, I use Rembrandt’s work as a metaphor for deep narrative work—encouraging clients to paint their internal stories in full, accepting shadows without judgment, illuminating forgotten parts, and embracing the richness that vulnerability brings. The power of your story lies not in hiding wounds but in integrating them as part of your authentic narrative.

Rembrandt’s legacy teaches that storytelling is a lifelong process—a continual layering and re-layering of experience and meaning. His portraits span youthful ambition to tender old age, proving stories evolve and, with courage, deepen over time.

The artist’s intimate self-examination offers us a masterclass: the journey to fully author your story demands radical honesty, self-compassion, and relentless curiosity. The story you tell yourself about yourself must hold space for paradox and truth.

Standing before a Rembrandt self-portrait, you witness a human saga written not in grand conquests but in quiet moments of self-awareness and revelation. This is the timeless power of storytelling. It shapes identity and connects souls, inviting you to own your story with the same fearless authenticity.

That is the enduring gift of Rembrandt—the power of your story is the power to see clearly within and share boldly without.

A story is our creation of a reality; indeed our story matters more than what actually happens. Is there really any difference, as someone famously asked, between the life of a king who sleeps twelve hours a day dreaming he’s a pauper, and that of a pauper who sleeps twelve hours a day dreaming he’s a king?

By ‘story’ I mean those tales we create and tell ourselves and others, and which form the only reality we will ever know in this life. Our stories may or may not conform to the real world. They may or may not inspire us to take hope – filled action to better our lives. They may or may not take us where we ultimately want to go. But since our destiny follows our stories, it is imperative that we do everything in our power to get our stories right.

For most of us, that means some serious editing.

To edit a dysfunctional story, you must first identify it. To do that you must answer the question: In which important areas of my life is it clear that I cannot achieve my goals with the story I have got? Only after confronting and satisfactorily answering this question can you expect to build new reality – based stories that will take you where you want to go.

Is this all starting to sound a little vague? I’m not surprised. But hold on. I understand you may be thinking Life as a story? The whole concept strikes you, perhaps, as a tad …. soft. I don’t look at my life in terms of story, you say. I disagree. Your life is the most important story you will ever tell, and you are telling it right now, whether you know it or not. From very early on you are spinning and telling multiple stories about your life, publicly and privately, stories that have a theme, a tone, a premise – whether you know it or not. Some stories are for better, some for worse. No one lacks material. Everyone’s got a story.

Caravaggio’s masterpiece The Calling of Saint Matthew powerfully illustrates the profound power of the story you tell yourself—the internal narrative that shapes your identity, your transformation, and your place in the world. From my perspective as Peter de Kuster, this painting vividly captures the moment when a life story is disrupted, rewritten, and renewed through conscious choice.

In the dim, shadowed tavern, Matthew sits counting coins, absorbed in a story of material security and social limitation, perhaps one of complacency and survival: “I am just a tax collector, separate from the sacred.” Into this mundane narrative bursts the figure of Christ, pointing with certainty, calling Matthew to a radically different self-story—the story of purpose, grace, and transformation. The light streaming profoundly illuminates Matthew’s face, capturing the precise instant he hears and internalizes his Call to Adventure.

This moment reveals storytelling’s supreme power: the story you tell yourself about who you are can be rewritten at any moment. Matthew’s journey moves from an identity rooted in numbers and risk to one of faith and courage. Caravaggio’s stark chiaroscuro—the clash of light and shadow—symbolizes the tension within our internal stories: old narratives fading into darkness, new truths breaking through into illumination.

Matthew’s surprised, almost reluctant gaze invites us to see the vulnerability inherent in narrative change. Transformation is never effortless or immediate. You must first hear the call, then wrestle with it internally before embracing a new version of yourself. This internal narrative dialogue is the crucible of growth.

The composition places viewers as witnesses and participants. We see ourselves in Matthew’s seat—counting our own coins, entrenched in our stories—yet invited to turn toward the light, to accept our call to transformation. Christ’s unambiguous gesture compels us: “Rewrite your story; step beyond the familiar.”

The narrative learns depth in Caravaggio’s inclusion of other figures, immersed in everyday tavern life. They represent old narratives—the familiar, the comfortable—that continue alongside Matthew’s radical shift. Our stories are always embedded within social contexts and histories, yet individual choice remains the spark for personal narrative revolution.

Caravaggio’s painting reveals that storytelling is not just retrospective but prophetic. The moment of calling is a portal; it abruptly alters the arc of the story, redefines identity, and aligns personal purpose with greater meaning. Your story is never fixed but awaits your conscious authorship to transform it.

The dramatic use of light reminds us that narrative clarity often comes as stark contrast—what was once hidden becomes visible. Your story gains power when it moves from shadow to illumination, when you own what was denied or overlooked. Like Matthew’s illuminated face, your awakening story creates new vision for self and action.

In my coaching, The Calling of Saint Matthew serves as living metaphor for moments clients face when their internal story fractures and demands revision—the crossroads of doubt and possibility. It teaches that embracing the call with both humility and resolve is the threshold to authentic transformation.

The painting’s intimacy—its raw realism and human scale—demonstrates that narrative transformation is not grand spectacle but deeply personal. Your story unfolds in these quiet moments of recognition and choice.

Caravaggio invites us to stand with Matthew and ask: What is my story? What call have I been ignoring? What light awaits me beyond the shadows of complacency and fear?

Your story, like Matthew’s, can pivot from survival to significance, from stasis to awakening. Through painting’s fierce contrast and urgent gesture, Caravaggio reveals storytelling’s greatest truth—the power to author your identity resides in the moment you choose to listen to your own calling and walk without hesitation into the light of possibility.

And thank goodness. Because our capacity to tell stories is, I believe, just about our profoundest gift. Perhaps the true power of the story metaphor is best captured by this seemingly contradiction: we employ the word ‘story’ to suggest both the wildest of dreams (it is just a story ……) and an unvarnished depiction of reality (okay, what is the story?). How is that for range?

The challenge? Most of us are not writers. ‘I am not a professional novelist’ one client said to me, when finally the time came for him to put pen to paper. ‘If this is the story of my life, you are damn right I’m intimidated. Can you give me a little help in how to get this out? That’s what I intend to do with the Hero’s Journey and The Heroine’s Journey project. First, help you to identify how pervasive the story is in life, your life, and second, to rewrite it.

Every life has elements to it that every story has – beginning, middle, and end; theme; subplots; trajectory; tone.

Michelangelo’s work on the Sistine Chapel ceiling is a profound narrative of human potential, struggle, and divine inspiration, encapsulated in one of the most monumental artistic achievements of the Renaissance. This masterpiece is not just a religious tableau; it is the story Michelangelo told himself about the power of perseverance, imagination, and the transformative role of the artist as a creator of worlds. His journey to complete the ceiling reflects a heroic personal saga where talent, faith, and relentless determination converge to redefine what art—and ultimately human potential—can be.

Michelangelo was commissioned by Pope Julius II in the early 16th century to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, a task that was both physically grueling and artistically challenging. The scope of the project was overwhelming, yet Michelangelo embraced the challenge, telling himself a narrative of endurance and genius: that through sheer will and vision, he could elevate human achievement to new heights. His story as he painted was one of a solitary hero, defying physical pain and artistic doubt, to realize an unprecedented vision of the cosmos and the human condition. This reflects the power of the story we tell ourselves—one of overcoming adversity by channeling inner strength and creativity into something lasting and transformative.

The ceiling depicts scenes from Genesis, the creation of man, and the fall and redemption of humanity, highlighting themes of creation, knowledge, and divine-human connection. Michelangelo’s portrayal of figures like God, Adam, and the prophets is not only a religious story but also a metaphor for human potential and the quest for meaning. The iconic image of God reaching out to give life to Adam symbolizes the profound connection between divine spark and human agency, mirroring Michelangelo’s belief in the creative power within every individual. His work invites us to recall the story we tell ourselves about our own ability to create, to shape life, and to connect with something greater than ourselves.

Michelangelo’s story as an artist was also about redefining the role of the creator. He saw himself not just as a craftsman but as a visionary who shaped reality through art. The complexity of composition, the bold use of anatomy, and the dynamic poses exemplify his mastery and his conviction that art could convey the divine drama of existence. Through this narrative, Michelangelo teaches that every individual has the power to transcend limitations and create something of lasting significance, a story echoed in the labor and genius poured into the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Ultimately, Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling is a celebration of human dignity and creative power, told through the story he lived and painted. It challenges viewers to consider the stories they carry about their own potential: Will it be a story of surrender or of heroic creation? The ceiling’s blend of divine inspiration and human effort stands as a testament to the power we hold when we tell ourselves a story of strength, purpose, and transcendence—transforming challenges into masterpieces that endure across time.

Through Michelangelo’s grand narrative on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the power of your story emerges: your narrative is the brush with which you paint your destiny, the force that turns struggle into artistry, and the vision that connects you to the divine and to your highest potential.

Story is everywhere in life. Perhaps your story is that you are responsible for the happiness and livelihoods of dozens of people around you and you are the unappreciated hero. If you see things in more general terms, maybe your story is that the world is full of traps and misfortune – at least for you – and you’re the perpetual victim (I’m always so unlucky…. I always end up getting the short end of the stick…. People can’t be trusted and will take advantage of me if I give them the chance.).

If you are focused on one subplot – business say – then maybe your story is that you sincerely want to execute the major initiatives in your company, yet you are restricted in some essential way and thus can never get far enough from the forest to see the trees. Maybe your story is that you must keep chasing even though you already seem to have a lot (even too much) because the point is to get more and more of it – money, prestige, power, control, attention. Maybe your story is that you and your children just can’t connect. Or your story might be essentially a rejection of another story – and everything you do is filtered through that rejection.

Stories are everywhere. Your body tells a story. The smile or frown on your face, your shoulders thrust back in confidence or slumped roundly in despair, the liveliness or fatigue in your gait, the sparkle of hope and joy in your eyes or the blank stare, your fitness, the size of your gut, the tone and strength of your physical being, your overall presentation – those are all part of your story, one that’s especially apparent to everyone else. We judge books by their covers not simply because we are wired to judge quickly but because the cover so often provides astonishing accurate clues to what is going on inside. What is your story about your physical self? Does it truly work for you? Can it take you where you want to go in the short term? How about ten years from now? What about thirty?

Édouard Manet’s Olympia is a bold confrontation with the power of the story you tell yourself—the story of identity, agency, and societal gaze—and how that story shapes perceptions, power dynamics, and self-presentation. From my perspective as Peter de Kuster, this painting stands as a landmark narrative moment, challenging entrenched myths and inviting radical self-authorship.

Manet’s Olympia presents a reclining nude woman, gaze direct and unabashed, unmasking the traditional passive female subject of art. Olympia’s story to herself and others is one of ownership: “I own my body, my purpose, and my narrative.” Her eyes meet the viewer’s without apology or shame. This is storytelling sovereignty—claiming your story fully even when society contests or attempts to rewrite it.

The painting’s scandalous reception underlines storytelling’s cultural power. Olympia rejects the myth of delicate, idealized beauty, embodying raw, real identity. Manet’s brushstroke reveals her as both subject and author, a woman telling her story to disrupt and redefine artistic and social narratives. This speaks directly to the stories we author about ourselves amid external pressures to conform or hide.

Olympia’s cat and black servant convey additional narrative layers—symbols of independence, domesticity, and contrasting social roles. These invite reflection on intersecting stories of race, class, and gender, revealing that storytelling is intricately social and political. Our self-story never exists apart from collective narratives that simultaneously constrain and enable.

The composition centers on touch, gaze, and gesture: Olympia’s poised hand holding flowers, her calm yet provocative expression, the direct light illuminating her skin. These elements weave a story of agency and defiance. Like Olympia, your story is wielded with intention—what you reveal, how you look back, what you hold close is your narrative language.

Manet’s unapologetic realism invites us to embrace our stories authentically, flaws and all. The power of your internal narrative lies not in perfection but in honesty and courage to appear as you truly are. Olympia teaches us to meet the gaze of the world on our own terms, telling a story that can rewrite norms and command respect.

In coaching, Olympia exemplifies the challenge clients face in claiming personal stories amid societal expectations. It reminds us that true change begins when you dare to face yourself fully and tell your story unapologetically—to yourself first, then others.

The painting remains a modern beacon for narrative agency. Through Olympia, Manet challenges every individual: what story do you own? How do you respond when culture tries to script you differently?

Ultimately, Olympia enshrines the power of your story as one of self-possession and radical truth-telling, a narrative bold enough to unsettle traditions and brave enough to transform lives.

You have a story about your company, though your version may depart wildly from your customer’s or business partners. You have a story about your family. Anything that consumes our energy can be a story, even if we don’t always call it a story. There is the story of your relationship. The story of you and food, or you and anger, or you and impossible dreams. The story of you, the friend. The story of you, your father’s son or your mother’s daughter. Some of these stories work and some of them fail. According to my experience, an astounding number of these stories, once they are identified, are deemed tragic – not by me, mind you but by the people living them.

Like it or not, there will be a story around your death. What will it be? Will you die a senseless death? Perhaps you drank too much and failed to buckle your seat belt and were thrown from your car, or you died from colon cancer because you refused to undergo an embarrassing colonoscopy years before when the disease was treatable. Or after years of bad nutrition, no exercise, and abuse of your body, you suffered a fatal heart attack at age fifty – nine. ‘Senseless death’ means that it did not have to happen when it happened; it means your story did not have to end the way it ended. Think about the effect the story of your senseless death might have on your family, on those you care about who you are leaving behind. How would that story impact their life stories? Ask yourself, Am I okay dying a senseless death? Your immediate reaction is almost certainly, “No!, of course not!

I’m not trying to be morbid. Story – which dies if deprived of energy – is not about death but life. Yet if you continue to tell a bad story, if you continue to give energy to a bad story, then you will almost assuredly beget another bad one, or ten. Why is abuse so commonly passed from one generation to the next? How much is the recurrence of obesity, diabetes and certain other diseases across families a genetic predisposition, and how much is the repetition of a dangerous story about food and physical exertion.

Banksy’s Girl with Balloon is a striking modern masterpiece that powerfully embodies the essence of the story we tell ourselves—the fleeting narratives of hope, loss, and the delicate interplay between holding on and letting go. From my perspective as Peter de Kuster, this iconic image reveals the narrative tension within us all and the profound impact the stories we craft have on our perception and resilience.

At the center is a young girl, reaching wistfully toward a scarlet, heart-shaped balloon drifting just beyond reach. This simple act of longing becomes a universal metaphor for human stories—the dreams and aspirations we nurture, the moments we grasp and sometimes lose, and the hope that propels us forward despite uncertainty.

This artwork powerfully illustrates that our internal narratives are in constant motion, subject to change and reinterpretation. The balloon can represent love, innocence, freedom, or lost opportunity—whatever story the viewer projects, reflecting the mutable nature of personal narrative. Your story may shift focus, evolve in meaning, and still hold its emotional core.

Banksy’s use of stark black-and-white figure contrasted with the bright red balloon underscores storytelling’s power of selective emphasis—what we illuminate in our internal narratives vs. what fades into shadow. This contrast invites us to examine which parts of our story we elevate with passion and which we let drift away.

The girl’s outstretched hand is a poignant gesture of both hope and acceptance—the tension between holding onto dreams and releasing control. This duality is the heart of many internal stories: how to balance desire with surrender, action with trust. The story you tell yourself must embrace this complexity to sustain resilience and growth.

Placed on urban walls, often fleetingly erased or updated, Girl with Balloon also speaks to narrative fragility and renewal. Stories are alive and interactive—they respond to context, challenge authority, invite reinterpretation. Your story, too, is not static but shaped by the spaces and communities it inhabits.

Moreover, Girl with Balloon embodies the democratization of storytelling. Public, accessible, sometimes ephemeral, it whispers that everyone holds the power to author and share stories that move and inspire collectively. Narrative agency does not belong solely to the powerful but to any voice daring to reach.

In coaching, I evoke this image to illustrate the delicate balance clients must find between clinging to aspiration and embracing change—the ongoing narrative dance of hope and acceptance.

Banksy’s work teaches that the power of your story lies not only in its content but in its capacity to invite connection, to evoke emotion, and to adapt. Every story contains moments of joy, loss, and rebirth—Girl with Balloon distills these into a poetic visual narrative that resonates deeply across cultures and generations.

Ultimately, Banksy’s masterpiece is a call: tell your story with both passion and openness, hold onto your dreams lightly, and trust in the transformative power of narrative to carry you forward, even when the balloon drifts beyond reach.

That is the power of your story—the story that rises and floats, sometimes slipping away, yet always beckoning you to keep reaching.

Unhealthy storytelling is characterized by a diet of faulty thinking and, ultimately, long – term negative consequences. This undetectable, yet inexorable progression is not unlike what happens to coronary arteries from a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet. In the body, the consequence of such a diet is hardening of the arteries. In the mind, the consequence of bad storytelling is hardening of the categories, narrowing of the possibilities, calcification of perception. Both roads lead to tragedy, often quietly.

The cumulative effect of our damaging stories will have tragic consequences on our health, engagement, performance and happiness. Because we can’t confirm the damage our defective storytelling is wreaking, we disregard it, or veto our gut reactions to make a change. Then one day we awaken to the reality that we have become cynical, negative, angry. That is now who we are. Though we never quite saw it coming, that is now our true story.